New Books from Brooke McEldowney

by GoComicsA special blog post from 9 Chickweed Lane and Pibgorn creator Brooke McEldowney

Introduction from "On Alternate Thursdays I Surrender My Body to Satan."

As I evolve new anthologies and graphic novels, the act of conferring titles upon them can be rather like cutting the maverick book from the herd, hog-tying it and searing my brand to the cover -- although with greater languor than any self-respecting cowboy would admit to. The trick, however, lies in coming up with the brand. My first editor instructed me years ago that the best method for arriving at a title is to amble idly through the massive accretion of cartoons for publication, rooting out dialogue and gag lines that strike me as meet for a potential title.

The process of culling titles from 52 weeks of cartoons can be daunting, so this part I left to my daughter, who made up two pages of aspirants, along with notes vis-нж-vis her opinion as to the suitability of certain prospects. When she came up with the possibility of the present title of this book, she offered only the hand-written and darkly ominous caution, "Not recommended."

Naturally, it was this title, "On Alternate Thursdays I Surrender My Body to Satan," that I took to my bosom as I might a stray puppy. Knowing from my 22 years of syndicated cartooning that the name Satan had been a no-no, never to be visited on a feature editor's desk, my daughter had visions of squads of ski-masked Episcopalian acolytes crawling ninja-style through the crabgrass approaching our house, katanas unsheathed, bent on my swift decollation in the driveway; she feared witness relocation, a new identity, a career in New Mexican septic tank maintenance.

I tried to point out that in the intervening years since I took up my syndicated nib, things had vastly changed; that editors were now so cool with the Prince of Darkness that their offices were festooned with pentagrams, runic curses and sacrificial virgins (if any indeed could be scared up) lazing about on the furniture until the cows came home. However, she took my reassurances with a narrowed gaze, especially the part about the virgins and cows.

I hung tough, though, and designed the cover dominated, as you can see, with the massive word

Satan.

My daughter has ordered some pamphlets on septic tank maintenance.

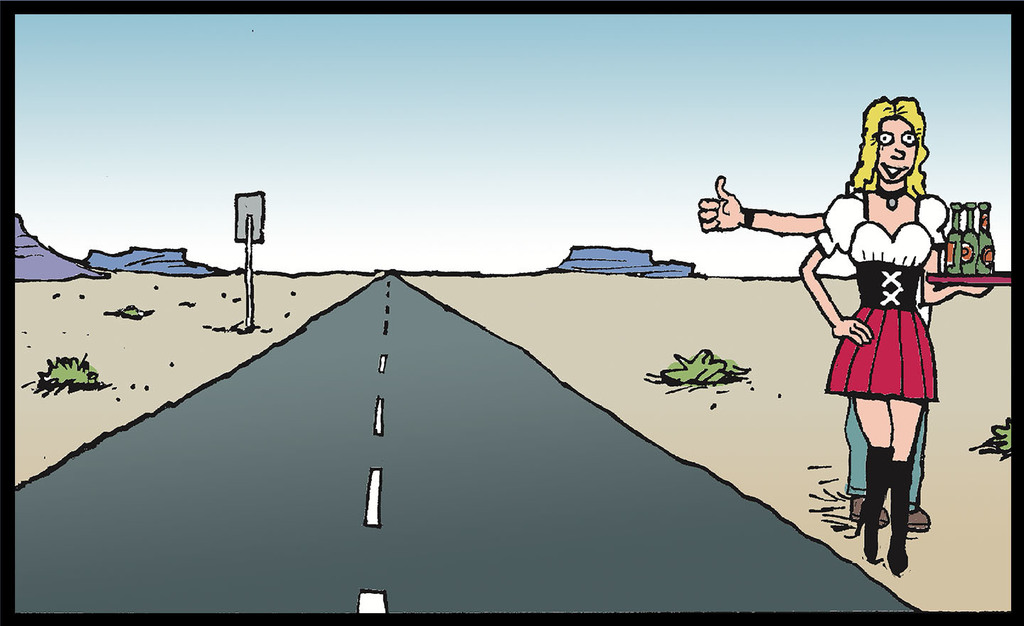

Introduction to second edition of "Edie Ernst, USO Singer - Allied Spy."

On the bookshelf across the room from me - just above the dictionaries and next to a rank of black vinyl LPs now looking like friendly old non-digital dinosaurs - rests a disparate accretion of cartoon anthologies, some tall, some impressively bound, jostling each other for attention, elbowing the smaller ones aside. If you squint you can just make out among them, sandwiched but self-possessed, a thin, yellow volume entitled "Male Call," by Milton Caniff. I found this book among my father's possessions after his death in 1998. Its pages are of cheapest newsprint, consistent with wartime rationing, and display cartoons originally distributed in camp newspapers to GIs during World War II. The strips, as the cover happily attests, feature "the effortless war activities of Miss Lace," a pneumatic siren with a penchant for the non-commissioned, limned in Caniff's trademark style.

I am glad to have this book, most of all because the inside front cover bears the inscription, neatly penned in 1945, "Ens. Thomas C. McEldowney U.S.N.R." It is the signature of my father, then a 19-year-old ensign in the navy during the final year of "The War."

Those of you who grew up when I was growing up remember that term: The War. It meant our parents' youth. World War I was spoken of, and, as time progressed, Korea and Vietnam; but "The War" was different. It belonged to the people who raised us. It was distinct, redolent of charismatic leaders - Churchill, Roosevelt, Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini - but, most of all, it was populated by all our parents; and not as we knew them. They were young, thrust without choice into a struggle that became their touchstone in adulthood. They did not wish war ever to be visited upon their children, but for them "The War" was who they were, summed up in two syllables. In my teens, while boys were being fed as cannon fodder into a muddled and protracted conflict that was so terribly questionable, "The War" remained a measure of the indisputable for our parents.

When I think about it now, "The War," for them, never really ended. It was when many of our parents were emerging from their teens, and possibly the most alive they would ever remember being.

As the story of Edie Ernst evolved in newspapers and online, it became a way for my readers to see their parents, or grandparents, as they were when they were young. Gran was no longer an old, cranky woman, but a slip of a girl traveling with the USO and singing to soldiers in camp shows while throughout the world all hell broke loose. The story, much more than an adventure and a romance, became a hail and farewell to all the people who bore us. And for me that was to remember my father before I knew him: a 19-year-old ensign serving his country on an aircraft carrier in the North Atlantic, and forking over a bit of his pay in 1945 for a compilation of "Male Call."

To him this book - "Edie Ernst, USO Singer - Allied Spy" - is dedicated, as well as to all the people of that generation as we never really encountered them: homesick, happy, busy, bored, right, wrong, struggling through war, waiting for peace, doing their best. The story of Edie Ernst is a complete fiction, but somehow it has allowed me to recollect somebody who raised me, and to say goodbye.

Another recent release from Brooke:

Purchase Brooke"їs new books here. Or, read 9 Chickweed Lane and Pibgorn.