Peter Mann (The Quixote Syndrome)

by GoComicsThe following excerpt is from an interview with an ill-mannered journalist who invited me to coffee on the pretense of asking me a few questions about my comics. I present them to you, reader, not because I presume that you wish to know the sordid details of my life or the gruesome mechanics behind the gleaming faн_ade of a finished comic, but because I would like to show you how admirably I acquitted myself in the face of this man's boorish interrogation. May my rectitude serve as an example to the denizens of this World Wide Web.

~Peter Mann, author and longtime sufferer of The Quixote Syndrome

Loutish Journalist [LJ]: How did you come to cartooning in the first place?

PM: I came to cartooning after a boyhood at sea. At the tender age of eleven, while visiting San Francisco for the National Youth Spelling Bee, I was shanghaied by a buxom chaperone with a chloroform-laced kerchief. I awoke hours later aboard a packet on the Pacific with the business end of harpoon poking at my boot heel. My whaling apprenticeship had begun. But, as I realized years later, after I had been thoroughly brined with ocean water, caked with spermaceti, and perfumed with ambergris, my schooling in cartooning had also just commenced. In those empty hours after a catch, after the decks had been swabbed, the baleen stacked, and the blubber casked, I would nestle down in my coil of ropes with a rusty knife nicked from the galley and scratch the content of my mind's eye into the ivory tooth of whale.

LJ: Alright, alright, could you stop wasting everyone's time? Write your phony novel on your own time, bub. What say you just answer my questions truthfully and to the point?

PM: Oh. I just thought"...Okay.

LJ: I'll ask again: how did you come to cartooning?

PM: I only recently-as in, within the last year- started drawing comics with any regularity or seriousness of purpose. I've always enjoyed drawing since I was a kid and have been a compulsive doodler for as long as I can recall. At some point in my childhood I wanted to be a cartoonist, but it never felt like a singular burning desire. Instead, I always wanted to be a cartoonist-writer-artist-comedic actor-filmmaker-gentleman farmer, and I didn't really see a problem with that when I was 11 (I still have trouble seeing why that's a problem). But I clammed up sometime in middle school and my drawing went pretty much dormant through high school. Thankfully, I got back into it in college. I took a couple art classes and drew the comics page of Wesleyan's student paper with two friends for a little over a year before we got the sack. These comics were crude in both form and content. My most recurring strip was called "Fatty McJerkface," featuring the random and excessively violent exploits of a loathsome bully with a vulnerable core.

LJ: Ok, pal, let's not get too bogged down in the early years. No one wants to hear about the crap you made when you were a kid or, even worse, an attention-hungry brat in college.

PM: Right. Sorry.

LJ: Isn't it true the only reason you kept drawing after college was to evade the crippling anxiety of being a normal talentless dullard?

PM: Um, well, that and I liked drawing.

LJ: So then what? How did you go from being a fresh-faced college graduate with a wishy-washy interest in art and no real commitment to comics to a thirty-something-year-old man-child talking people's ear off about his "artistic process" ?

PM: After college, I got serious about making art, though I forgot about comics for a while. But I did so by going to graduate school in history-that is, after first spending two years doodling on beer coasters in Prague as an English teacher, followed by more doodling on post-it notes at various office jobs around San Francisco. A history PhD was a circuitous route to making art, I suppose, but I'm glad I did it. I got to read a lot of good books and soak my brain in the past, which has been fantastic for collecting raw material for stories and images. I studied Modern European Intellectual history so that I could sprawl across disciplines and study literature, art, philosophy, and history all at once. It was really a choice born of intellectual gluttony more than anything.

LJ: So that's why your comics are so pretentious and backward looking!

PM: Meanwhile, I was becoming increasingly wrapped up in printmaking: woodcut, linocut, lithograph, and etching. Ever since college, German Expressionism and early twentieth-century graphic art in general have been a huge influence. And since 2009, I've been steadily making prints and drawings and exhibiting them in local galleries in San Francisco. Most of my "fine art" work tends to have a similar historical/literary bent, since that's what I've been immersed in for the last several years of my life. My most recent big projects have been a print series of social types from turn-of-the-century San Francisco and a collection of drawings on every page (physically) of Don Quixote, which were covertly placed inside books in San Francisco bookstores.

LJ: So why did you all of a sudden start making comics? Was it because you realized you were mediocre hack of a woodcut artist?

PM: I still make prints and drawings, in addition to comics. But last fall I decided to throw myself into comics with a new project involving my day job. I teach in a freshman humanities program at Stanford called Structured Liberal Education, so I decided I would do a comic each week to go with one of the weekly readings from our syllabus. I also opened the challenge to my students and encouraged them to submit comics related to the course. I really enjoyed it. I found the syncing of syllabus and comic to be a helpful constraint for deciding what to draw that week, as well as a great way to engage with the text in a new, more playful way than teaching or scholarship. It was satisfying to have a weekly output to balance the input of heavy reading-at least that's my comics-as-enema theory of artistic creation. And the quick turnover is especially nice, in contrast to some of the other creative projects I'm currently slogging through. I also enjoy reading with a sense of creative purpose. Whether your purpose is to teach a class, draw a comic, write an essay or a novel, it can redeem some otherwise tough and recalcitrant reads. What I love about comics in particular is how so many different artistic domains merge on the page: not just visual art and writing and the wonderful alchemy between them, but also cinematic concerns of composing shots and stories in sequence. It's like Wagner's idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk without all the agonizing music.

LJ: Gesundheit! Look, I nodded off there for a while, but from what it sounds like, this whole comics thing is just a school assignment, huh?

PM: The first 30 comics from this year bear the indelible stamp of the syllabus I teach, but now I'm free to do whatever and am drunk with a sense of possibility. I plan to move into some longer serial projects this winter, but I still aim to keep The Quixote Syndrome in the same literary/historical ambit: often irreverent, occasionally profound, and always with a heavy dose of strange. There are so many stories to be fashioned and refashioned from the landfill of history, and I'm excited to keep rummaging. I still have a lot to learn about making comics along the way.

LJ: You can say that again! Did you even read any comics when you were a kid? You strike me as the kind of jerk who never read the Sunday funnies or comic books. Is that true?

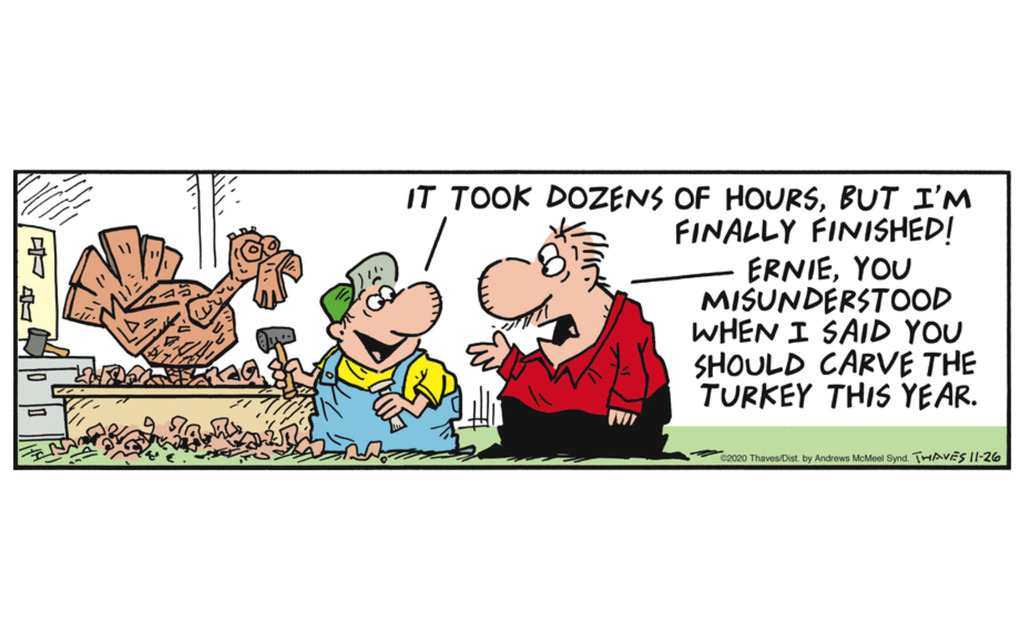

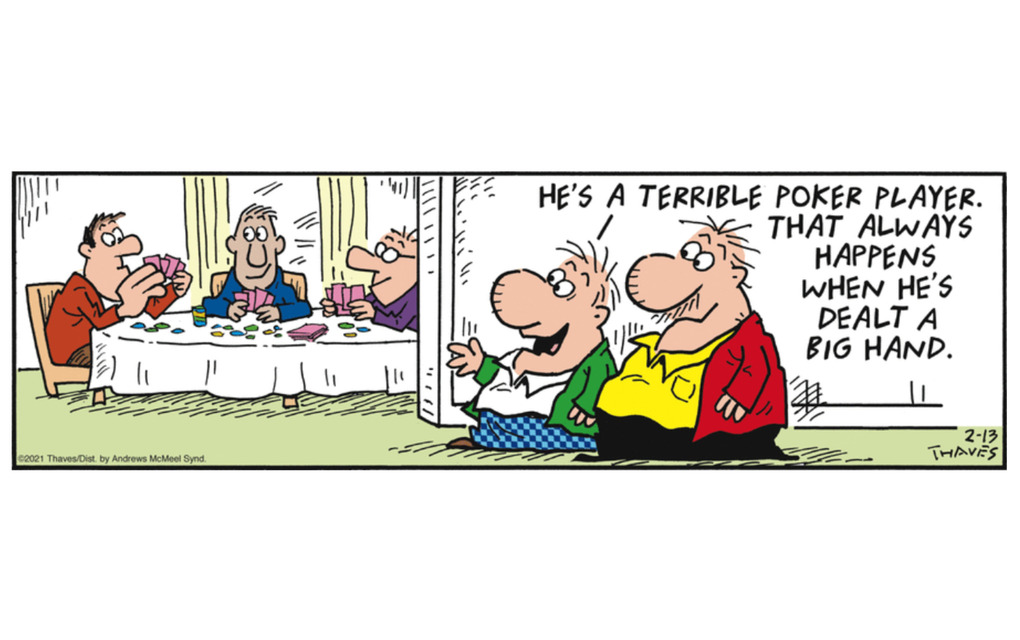

PM: Kind of. I'll admit I've never been into superheroes. My friends give me hell for it, but I just don't see the allure of stories about people with world-saving super powers. I much prefer stories about people with earthly powers and outsized neuroses. And while I was never a habitual reader of syndicated strips, I was a big fan as a kid (and still am) of book editions of Calvin and Hobbes and The Far Side. I even wrote Bill Waterson a fan letter when I was 10 or 11 years old. MAD and Cracked magazines also made a huge impression on me. So did a series of books called Illustrated Classics: Robin Hood, The Three Musketeers, Treasure Island, and the like, all abridged and illustrated for kids.

As an adult, the comic works I keep in my treasure chest are: everything by R. Crumb and Joe Sacco, Franz Mazereel's woodcut novels, George Grosz's Weimar era cartoons, Charles Burns's Black Hole, Art Spiegelman's Maus, Jason Lutes' Berlin series, Alison Bechdel's Fun Home, Scott McCloud's Understanding Comics, Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell's From Hell, the one-of-a-kind Vivian Girls of Henry Darger, and the brilliant and hilariously crude art of David Shrigley. I think in general I'm more drawn to long-form comics because I come to them from a novel-reading sensibility. That, and because it's the form I'd ultimately like to work in.

LJ: Alright, I can't stomach much more. Last question: do you ever worry that your sickeningly arcane subject matter will drive readers either away from your comics or to your house with pitchforks and bags of flaming feces?

PM: Nah. There's plenty of comics out there for everyone. And I live several floors up, high above the pitchforks and feces.

LJ: Well, there you have it folks: Peter Mann: comics greenhorn (someone buy this guy a straight ruler, please!), frustrated historian, and insufferable dilettante. In short, a real mess.

PM: Who are you talking to?

LJ: Shut up and finish your coffee.