A Firsthand History of ‘Bozo’, the World’s First Pantomime-Style Strip

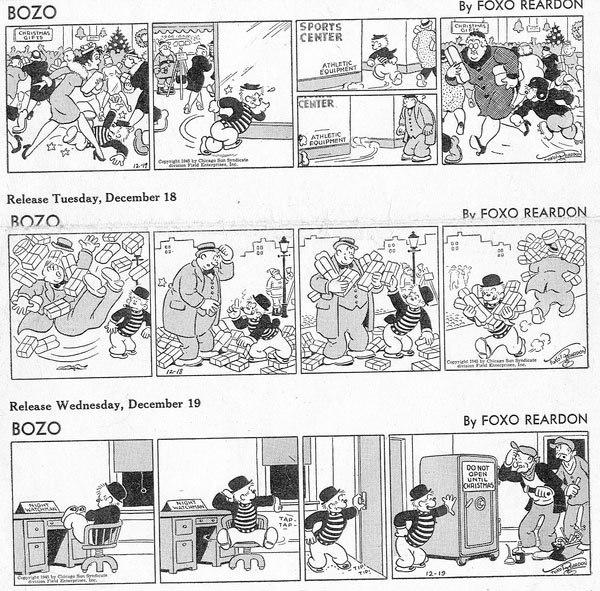

by GoComics TeamIn late 2020, we received an email from Michael Reardon, son of the late Francis X. “Foxo” Reardon. Had we heard of his father’s early 20th-century feature called Bozo, and would we like to run the entirety of it on GoComics? Michael asked. We dug through the archives and responded with a wholehearted yes. Starting in March 2021, we welcomed Bozo—the first pantomime-style comic strip—onto the site, which Foxo Reardon penned from 1921 until his death in 1955. (We began with the first syndicated strip, which ran in 1945.) Here, Michael shares firsthand history about his father and Bozo—and why he wanted to show this “nobody” character to the world nearly a century after Foxo first created him.

What was it like to grow up with a cartoonist as a father?

My father had been working as a professional cartoonist for sixteen years when I was born in 1937. He had worked the last fourteen of those years as a staff cartoonist for the Richmond (Virginia) Times-Dispatch, one of the South's leading newspapers, doing every type of cartooning: news, sports, humor, editorial, and creating a number of regularly published features, as well as working outside sketching assignments at the courts and at crime scenes.

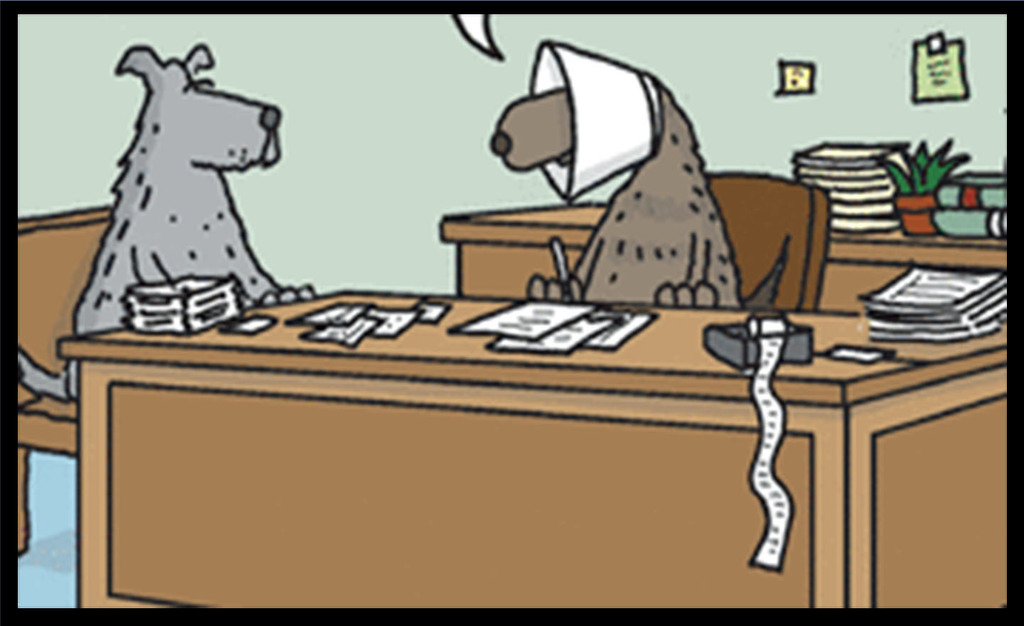

Among his created features was Bozo, the world’s original pantomime comic strip. He created that strip at age 16 in 1921 just after being laid off as sports cartoonist at the Times-Dispatch and before being rehired in 1923.

My father worked afternoon and evening hours at the paper. I was child number six, which meant my bedtime was earlier than that of my older siblings. I remember lying awake in bed alone and afraid in the dark, and the relief I felt when Dad returned home around 9 p.m. or so, his booming voice heard throughout the house as he relayed to my mother all the events of the day at the newspaper. Obviously, any bad guys would be chased off by that voice. And that voice was usually filled with enthusiasm and excitement. So, considering the hours that he worked, he was gone most of the day during my first eight years, but his zest for life had a definite impact on me. His voice reflected all the excitement of the world. So I knew there was a lot going on out there.

In 1945, at the end of World War II, my father became internationally syndicated with the Chicago Sun-Times Syndicate with his comic strip Bozo, which was always his first love. The strip had appeared weekly in the Times-Dispatch from at least 1925. Syndication was a big change for him and our family. He set up his drawing desk between the living room and dining room at home, and his presence was always there. When I came home from school, he was always there. Always there in the evening. I would stand there looking over his shoulder. He preferred working overnight hours, and he usually slept until early afternoon. Having been born into all this, I never realized the special person that he was until he passed away when I was 18. He never boasted of his position, never boasted of being one of the country's top pen artists, never boasted that Bozo was the syndicate’s most popular comic, as a survey of readers showed. In fact, he downplayed his importance in comparison to other cartoonists. A definite lesson in humility.

What was your favorite thing about Bozo?

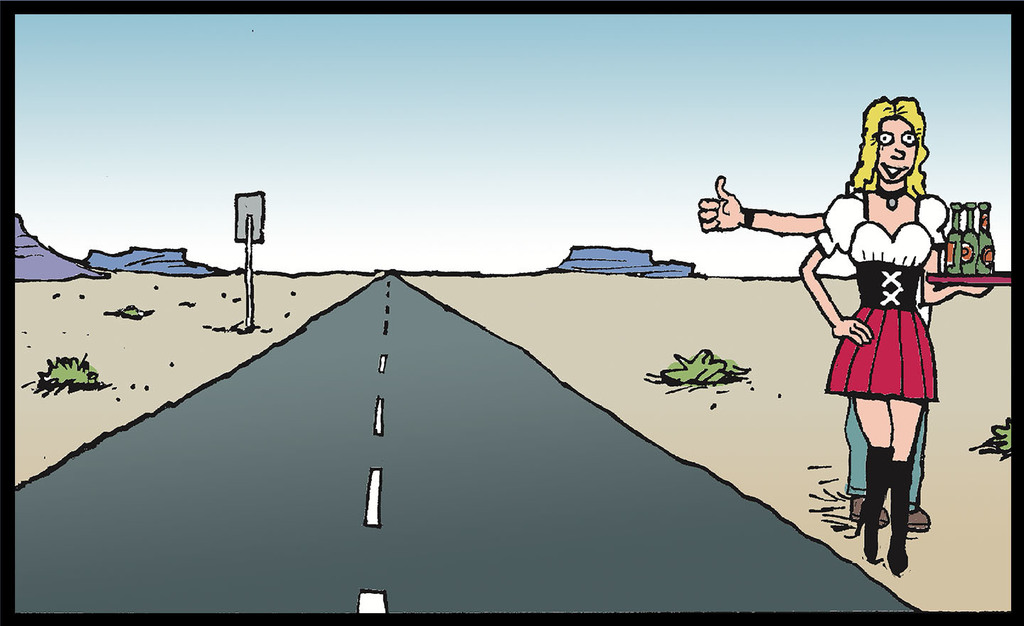

Bozo's uniqueness. There is no other character like Bozo. The syndicate described him as “America's roughneck.” Yes, a roughneck, but a lovable roughneck. My father described him as “a nobody.” If a little, short, unimpressive looking nobody like Bozo could overcome adversity, as he usually did, then there was definite hope for the rest of us. And then gracing many strips is Bozo’s girlfriend, the beautiful Bozann. Also, there is the mysterious “man with the umbrella,” appearing more often than not in the background.

What do you think today's audience will enjoy in Bozo?

Humor and excellent artwork is timeless and universal. I think that today’s audience will enjoy all the same things in Bozo that the audience in the ’20s, ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s enjoyed in the strip. All one has to do to get many enthusiastic answers to this question is to read the comments of the Bozo followers on GoComics. “Among humor comics, that is, those comics meant to be funny, Bozo stands out for its outstanding artwork. It is a complete comic which, with excellent perspective, gives as much attention in detail to the background scenes as to the foreground. Drawn in two dimensions, it gives a three-dimensional effect.” In the words of a number of Bozo followers, no other strip does that as well as Bozo.

Many think that if comedy isn't new or modern that it is of diminished value. I think that the opposite is closer to the truth. Where have all the great comedians gone: Milton Berle, Jimmy Durante, George Gobel, Bob Hope, Flip Wilson, Jack Benny, Jerry Lewis, Don Rickles, Jackie Gleason, and so many more? There were never greater comedians than them. The same can be said of the truly great classic cartoonists. Their work can't and won’t be surpassed, no matter how modern or “new” be those that follow. The Golden Age of Cartooning, the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s, was just that: golden.

To quote a Bozo follower from India: “Foxo Reardon was undoubtedly a very talented genius! I [am] gobsmacked that this comic stayed hidden for so long for so many, and nobody who speaks of great comics and great cartoonists ever say his name.”

Why do you want to get the comic back out into the world?

The four saddest words in the English language are “What could have been.” I remember my dad telling my mother that he intended to do Bozo “until at least 75.” He had no intention of retiring. And he intended for the strip to continue regardless. As he once told me, “I might die, but Bozo will not die,” referring to the expectation that another cartoonist would take over Bozo at his passing.

Sadly my father died of cancer at age fifty in 1955, after a two-year battle, and his dream of continuing Bozo for another quarter century came to an end. The syndicate could not find another cartoonist who could sufficiently copy my father’s style, a style developed over a period of 34 years. There was always a loss of newspapers when another artist took over the strip temporarily when he was out sick.

Another odd sixty years went by, and then I discovered GoComics. Those saddest words “What could have been” suddenly became the hopeful words “What might yet be.”

What else would you like our audience to know about Bozo or your dad?

My dad was a born cartoonist. He never held a job title other than that of “cartoonist.” It wouldn't be too much of a stretch to say that he was born with a drawing pen in one hand and a bottle of India ink in the other. He liked to tell the story of how he as a 16-year-old “sat on the editor’s doorstep every day” until he was finally hired. He loved his family and his country. He supported the civil rights movement before it became fashionable. He raised eight children—six sons and two daughters—all responsible citizens, which included a Jesuit priest and a pediatrician who served as a volunteer doctor for four years in Vietnam during the war there. All sons served in the military: three in the regular U.S. Marine Corps during the Korean War and three in the active reserves. Bozo was carried by Stars and Stripes, the newspaper of the U.S. Armed Forces and was popular with our men and women in uniform.

After Dad's passing, Ham Fisher, the creator of the Joe Palooka comic strip wrote my mother a long letter of condolence, several pages long, which he ended with the tribute, “I have known very few like him in a long lifetime.”

It is my profound hope that GoComics subscribers will make my dad's words, “Bozo will not die” a continuing reality.

Be sure to follow Bozo on GoComics, where it’s updated daily.